|

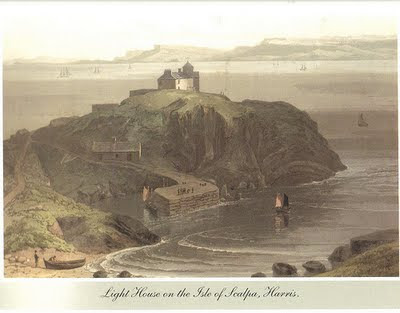

| Mingulay / Miughalaigh 1888 |

Another short historical anecdote taken down by Alexander Carmichael probably from the recitation of Roderick MacNeil, nick-named Ruairidh an Rùma, tells of the time when plague visited the remote island of Mingulay

About 300 years ago ten families lived in Mi[ng]ulay

One time in win[ter] the MacNeil of the day won[dered] that he

was see[ing] no per[son] from Mi[ng]u[lay]. He sent a boats crewOne time in win[ter] the MacNeil of the day won[dered] that he

to in[vesti]g[ate]. The boat came over and land[ed] and sent

up a man the name of MacPhie. When he came

to the houses which then stood on a rocky Bun[?]

N[orth] E[ast] of the pre[sent village] he found all within dead. He

ret[urned] to his com[panions] who were keep[ing] the boat. They as[ked]

him what news. I’ll tell that pre[sently] said Mac

Phi not a bone of your bone [recte: body] shall come

in till you tell us first. as he would

not do so the boat left him and ret[urned] to Cas[tlebay]

and told MacN[eil] For 7 w[eeks] no other boat was

able to come. In the mean[time] Mac[Phie] went to the

hill op[posite] Bearn[aray] where there was a hut where

the sheep shelt[ered] dur[ing] snow. He got hold

of some sheep skin and made a cov[ering]

for himself and used the fat of the sheep

when frozen as food. When MacN[eil] came fire

was set to all the huts and the dead bod[ies] were

burnt. MacN[eil] asked MacPh[ie] if he were

committed[?] an[d] live in Miul[ay]. He said he wo[u]ld

and chose 3 or 4 trust[y] frie[nds]. They built the

huts down on the stran[d] but from

this the pred[?ecessors] of the p[?opulatio]n had to remove

on acc[ount] of the en[croachment] of the sea. Ruary saw

a man to whose house the sea was

ap[proaching]. He left his old moth[er] in his [hut] and

had not got six y[ar]ds from the ho[use] when a

sea came and left not one stone.

Reference:

CW 114, fos. 63r –64v.

Image:

Mingulay / Miughalaigh 1888.